When a generic drug company wants to prove its product works just like the brand-name version, it doesn’t just guess. It runs a bioequivalence study. For years, the gold standard was simple: compare the maximum concentration (Cmax) and the total area under the curve (AUC) of drug levels in the blood. But for some drugs - especially long-acting, abuse-deterrent, or combo-release formulations - those two numbers weren’t enough. That’s where partial AUC comes in.

Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short

Imagine two painkillers. One releases its dose slowly over 12 hours. The other hits fast and fades. Both might have the same total AUC - meaning the body absorbs the same amount of drug overall. And both might have similar Cmax values - meaning the peak blood level looks the same. But here’s the problem: the fast-acting one could spike too high early on, raising abuse risk. The slow one might not reach effective levels fast enough to relieve pain. Traditional AUC and Cmax miss these differences entirely. This isn’t theoretical. In 2014, a study in the European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences found that 20% of generic drugs that passed old bioequivalence tests failed when partial AUC was applied. For products with modified-release profiles, that failure rate jumped to 40% when comparing fasting and fed conditions. The old metrics were too blunt. They measured the whole journey but ignored the critical turns.What Is Partial AUC?

Partial AUC - or pAUC - cuts the drug concentration-time curve into a specific window of time that matters most. Instead of looking at the entire 24-hour curve, you focus only on, say, the first 2 hours after dosing. Or maybe the time when drug levels are above 50% of the peak. Or the period right after absorption begins, before distribution kicks in. The key idea? Measure what’s clinically relevant. For an opioid painkiller with abuse-deterrent properties, the first hour after ingestion is critical. If the generic version releases too much drug too fast during that window, it could be snorted or injected - defeating the safety feature. pAUC catches that. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration started pushing for pAUC in 2013, following guidance from the European Medicines Agency. By 2018, the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research made it a priority. Today, over 127 specific drug products have official FDA guidance requiring pAUC analysis. That number keeps growing - 41 new products were added in 2023 alone.How Is pAUC Calculated?

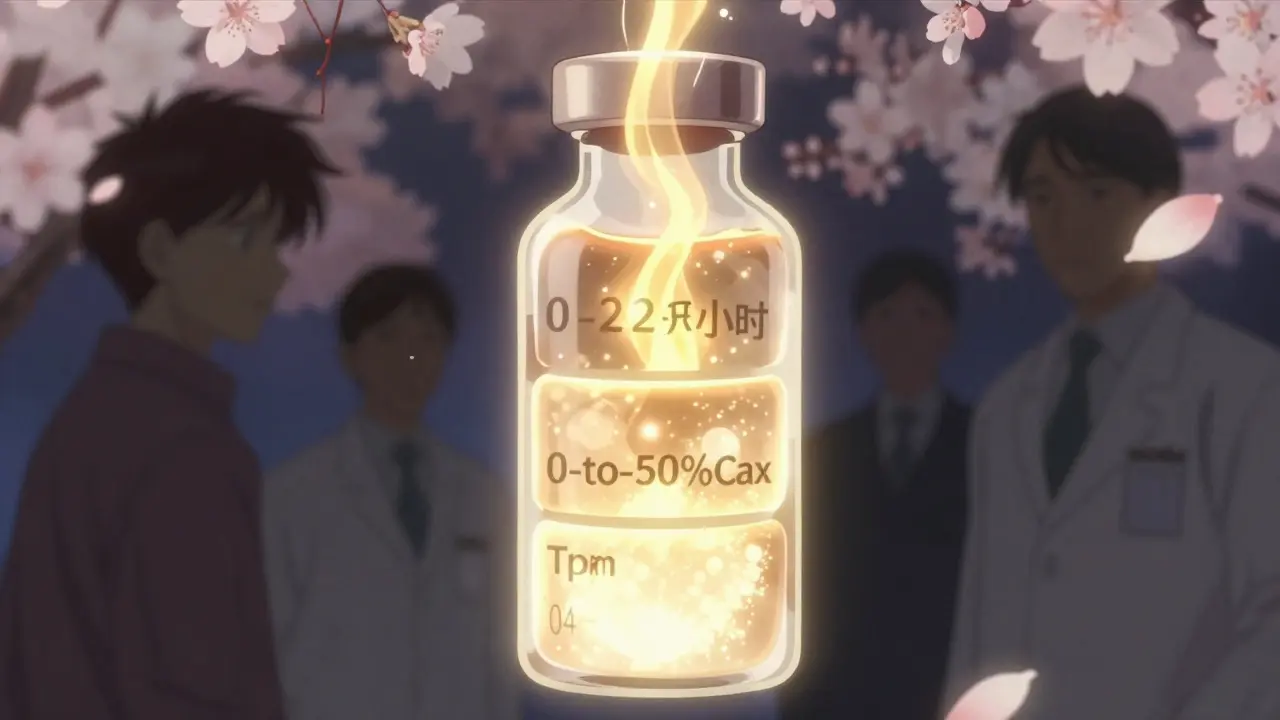

There’s no single way to define the “partial” window. It depends on the drug and its purpose. The FDA says the cutoff time should be tied to a clinically relevant pharmacodynamic effect - meaning, when does the drug start working? When does it stop being safe? That’s not always obvious. Three common methods are used:- Time-based: Measure from 0 to 2 hours, or 0 to 4 hours. Used for fast-acting drugs.

- Cmax-based: Measure from 0 to the time when concentration hits 50% of Cmax. Helps focus on absorption.

- Tmax-based: Use the average time to peak concentration from the reference product as the endpoint. Best when Tmax varies widely between subjects.

Why It’s Hard to Use

pAUC sounds simple - until you try to implement it. First, defining the time window is messy. FDA product-specific guidances vary wildly. Only 42% of them clearly say how to pick the cutoff. That leaves companies guessing. In 2022, 17 ANDA submissions were rejected because the pAUC window didn’t match regulatory expectations. Second, pAUC is noisier. Because you’re zooming in on a smaller part of the curve, variability goes up. A 2020 study found that studies using pAUC often need 25-40% more participants than traditional ones. One Teva biostatistician said switching to pAUC for an extended-release opioid generic pushed their study size from 36 to 50 subjects - adding $350,000 to development costs. Third, you need specialized skills. Most biostatisticians aren’t trained in pAUC. A 2023 BioSpace survey found that 87% of job postings for bioequivalence roles now list pAUC expertise as required. Tools like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM are mandatory. And even then, the statistical methods - like the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller confidence interval - aren’t taught in most pharmacology programs.Where It’s Most Important

pAUC isn’t needed for every drug. But it’s critical for certain categories:- Central nervous system drugs - 68% of new submissions use it. Think ADHD meds, sleep aids, anti-seizure drugs.

- Pain management - 62%. Especially opioids with abuse-deterrent coatings.

- Cardiovascular agents - 45%. Beta-blockers, long-acting antihypertensives.

The Bigger Picture

The push for pAUC reflects a shift in how regulators think about generic drugs. It’s no longer enough to say “the same amount gets absorbed.” You have to prove how it gets absorbed - and whether that matches the original. The FDA is working on solutions. In early 2023, they launched a pilot using machine learning to automatically suggest optimal pAUC time windows based on reference product data. That could cut down guesswork. But until then, companies are stuck navigating a patchwork of guidelines. The global bioequivalence market is growing fast. In 2022, 35% of new generic drug applications included pAUC - up from just 5% in 2015. By 2027, Evaluate Pharma predicts that number will hit 55%. Companies that don’t invest in pAUC expertise will fall behind.What You Need to Know

If you’re developing a generic drug:- Check the FDA’s product-specific guidances. If your drug is listed, pAUC is likely required.

- Don’t assume the time window is obvious. Use pilot data or published reference profiles to define it.

- Plan for larger sample sizes. Budget extra time and money for statistical analysis.

- Work with biostatisticians who’ve done pAUC before. Don’t rely on someone learning it on the job.

- Understand that not all generics are equal - especially for complex formulations.

- Don’t assume bioequivalence means identical performance. pAUC helps ensure that.

- When patients report unexpected side effects or lack of effect with a generic, consider pharmacokinetic differences - pAUC might explain why.

Final Thought

pAUC isn’t just a fancy statistic. It’s a safety tool. It closes a dangerous gap in how we judge generic drugs. For drugs where timing matters - whether it’s preventing abuse, ensuring steady pain relief, or avoiding seizures - it’s the difference between a safe product and a risky one. The science is solid. The regulatory push is real. The cost is high. But the cost of getting it wrong? That’s measured in patient harm.What is partial AUC in bioequivalence studies?

Partial AUC (pAUC) measures drug exposure only during a specific, clinically relevant time window - not the entire concentration-time curve. It’s used when traditional metrics like Cmax and total AUC can’t detect differences in how fast or when a drug is absorbed, especially for extended-release or abuse-deterrent formulations.

Why is pAUC needed instead of total AUC?

Total AUC tells you how much drug was absorbed overall, but not when. For drugs like long-acting opioids or ADHD medications, the timing of absorption matters for safety and effectiveness. A generic might have the same total exposure but release too quickly at first - increasing abuse risk or side effects. pAUC catches those differences.

How do regulators decide the time window for pAUC?

The FDA recommends linking the time window to a clinically relevant pharmacodynamic effect - for example, when the drug starts working or when peak effects occur. Common methods include using the reference product’s Tmax, setting a cutoff at 50% of Cmax, or using fixed time intervals like 0-2 hours. But there’s no universal rule - each product’s guidance must be checked.

Is pAUC required for all generic drugs?

No. pAUC is only required for specific drug products with complex release profiles - like modified-release opioids, CNS drugs, or combination formulations. As of 2023, over 127 products have FDA guidance requiring pAUC. Most standard immediate-release generics still use only Cmax and total AUC.

Why do pAUC studies cost more and need larger sample sizes?

Because pAUC focuses on a smaller part of the concentration curve, variability increases. Small differences in absorption timing become more noticeable, making results noisier. To compensate, studies need more participants - often 25-40% more than traditional studies - to maintain statistical power. This drives up costs and complexity.

What skills are needed to run a pAUC analysis?

You need expertise in pharmacokinetic modeling (using tools like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM), advanced biostatistics (including Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller methods), and deep knowledge of FDA product-specific guidances. Most biostatisticians require 3-6 months of additional training to become proficient. Job postings for bioequivalence roles now routinely list pAUC as a required skill.

What happens if a company uses the wrong pAUC time window?

The FDA may reject the ANDA application. In 2022, 17 submissions were denied specifically due to inappropriate pAUC time interval selection. This can delay approval by months or years and cost hundreds of thousands in rework. Always follow the product-specific guidance exactly - and if it’s unclear, consult with regulators early.