DAW Prescription: What It Means and How It Affects Your Medication

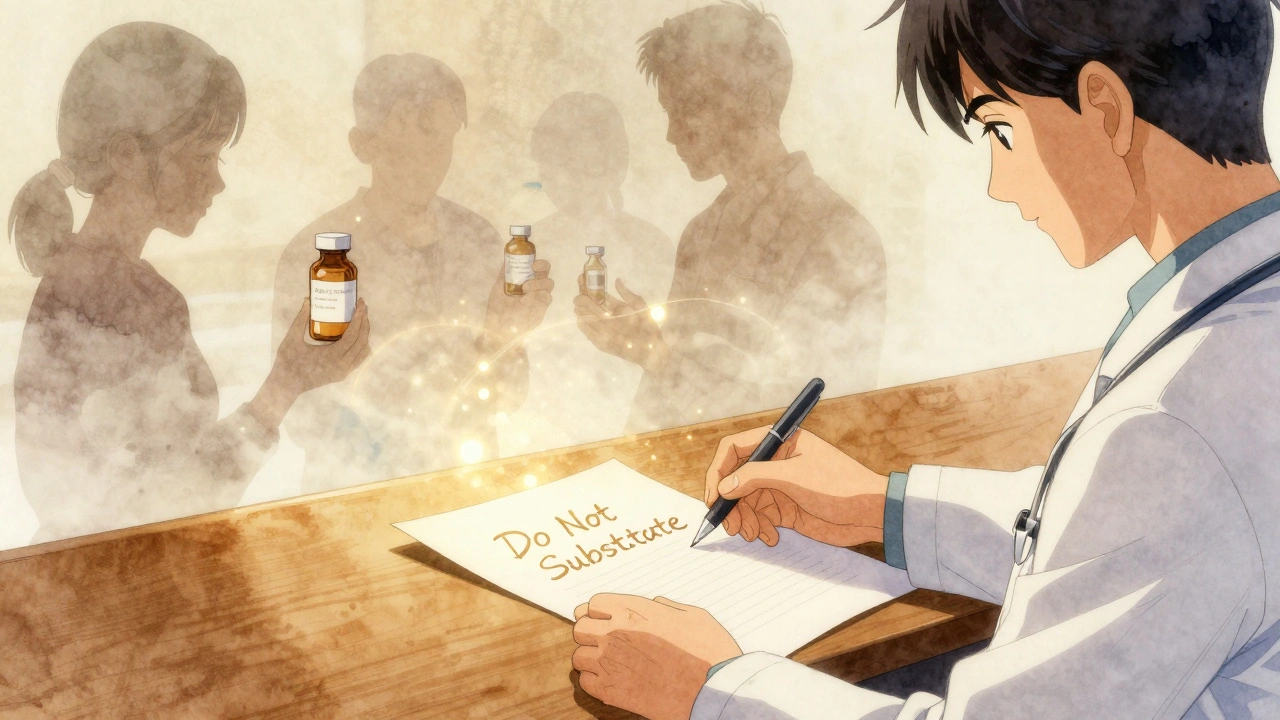

When you see DAW prescription, a code on your prescription that tells the pharmacy whether substitution of brand-name drugs with generics is allowed. Also known as Dispense As Written, it's not just a formality—it directly affects what you pay and what you get at the counter. If your doctor checks DAW 1, you’ll get the exact brand-name drug, no matter the cost. If it’s DAW 0, the pharmacist can swap it for a cheaper generic without asking. This small code shapes your out-of-pocket expenses, especially when brand-name drugs cost ten times more than their generic versions.

DAW codes aren’t random—they’re tied to state laws, insurance rules, and sometimes even the doctor’s intent. In some states, pharmacists are required to substitute generics unless the prescription says otherwise. In others, the prescriber must explicitly block substitution. That’s why you might get a generic one month and the brand name the next, even with the same prescription. It’s not a mistake—it’s the system at work. And if your doctor wrote "DAW 1" because they believe the brand works better for your condition, that’s a clinical decision worth understanding. But in most cases, especially for common drugs like statins, blood pressure meds, or antidepressants, generics are just as safe and effective, according to FDA standards.

DAW prescription rules connect to broader issues like generic substitution, the practice of replacing brand-name drugs with chemically identical generics approved by regulators, and pharmacy dispensing, how pharmacies follow legal and insurance guidelines when handing out medications. These aren’t just behind-the-scenes processes—they impact whether you can afford your meds at all. For example, if your insurance denies coverage for a brand-name drug and your prescription doesn’t allow substitution, you’re stuck paying full price. But if DAW is set to allow substitution, the pharmacist can step in and save you hundreds a month.

Some people worry generics are inferior. But the data doesn’t back that up. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They’re tested for bioequivalence—meaning they work the same way in your body. The only differences are in fillers, color, or shape. For most people, that’s irrelevant. But for a few conditions—like epilepsy, thyroid disorders, or blood thinners—tiny variations can matter. That’s why doctors sometimes specify DAW 1. Still, in over 80% of cases, generic substitution is not just safe—it’s smarter.

What you’ll find below are real-world examples of how DAW prescriptions play out in daily care. From how PBS in Australia handles generic switches, to how U.S. pharmacy systems enforce substitution rules, to how drug interactions can change when a generic is swapped, these posts give you the tools to ask the right questions. You’ll learn how to read your prescription label for DAW codes, when to push back on a pharmacy’s substitution, and how to talk to your doctor about whether your drug really needs to be brand-name. This isn’t theory. It’s about controlling your medication costs and making sure you get what works—without overpaying.